Joi Weaver:

It’s always tempting, when talking of influencing culture, to buy into the “magic bullet” theory, the idea that a single cultural item will change the course of the society. “Oh,” we might say, “if only someone would make the perfect movie about space exploration, or write the perfect novel, or create the perfect painting, then everyone would understand!”

Of course, these “magic bullets” never actually work. You may get millions to see a movie like Apollo 13, but only a small percentage will become fans of space exploration because of it. Books like Roving Mars will convince a few of the need for further exploration, but only a few.

Influencing culture turns out to be more like creating a stalagmite than hitting a target. Trillions of drops of water, over thousands of years, slowly form a beautiful, lasting pillar inside a cave. In the same way, thousands of stories, in every medium, over decades and centuries, will slowly build up an idea in a culture, the picture of space as our playground, our backyard, our home.

The stories that will inspire the human race to reach for the stars cannot come only from the experts and the big-budget movie makers. The stories that will change the world have to come from us, the stories we tell our friends and neighbors as we point out the ISS in the night sky, the stories we dream up as teenagers and scribble into notebooks in college.

In this case, even a poor story may be better than no story at all. The poorest space story is still another drop of water, another point of data, another element in the construction of the narrative.

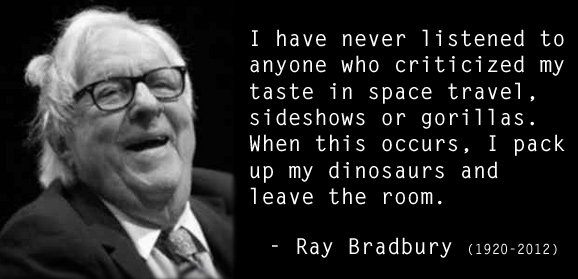

So what are you waiting for? It may not matter if you’re the next Ray Bradbury, or if only your mom reads your story: you can still influence someone.

Signups have begun for National Novel Writing Month, a free online challenge in which participants pledge to write a 50,000 word novel in the month of November. If you finish the month with 50,000 words, you win. There are thousands of winners every year: your prize is the satisfaction of having written a novel. Thousands of people are already telling their stories, and now is the time to contribute ours. Sign up, write a book about Mars colonization, or space exploration, or anything that you think will move the culture forward even the tiniest amount. It may be only a drop in the ocean, but we need every drop we can get.