Ill-informed Moderator: “It’s a wonderful buzz, it’s wonderfully exciting. But…ah…space travel costs billions…ah, how real is it…as a business model?”

Category Archives: Transcripts

"New Visions for Humans in Space" – Planetfest 2012 Panel Discussion

Peter Diamandis: “There is plenty of cash on this planet. Plenty of private capital. That was born in the fifties and sixties, inspired by space, who now are saying, ‘You know, I can’t take it with me, let me make a big change and invest and go into the space frontier.'” I have a question for the audience…if you had a shot of going on a one-way trip to Mars, and you had a seventy five percent chance of landing safely and living there – seventy five percent – how many folks would go on a one way trip to Mars? Raise your hand. Okay, now, hear me out…it’s a fifty-fifty shot now. How many of you in the audience that have your hands up on a fifty-fifty shot actually have a graduate degree? Ok, we’ve got plenty. Enough for a crew at least.

Concept and Promotional Videos for Planetary Resources (and others)

Asteroid Mining Mission Overview (Subtitled in Any Language)

“Since 2010, a world-class team has been quietly working to expand humanity’s resource base. Their path forward is to mine asteroids that have high concentrations of water and precious metals.

Everything we hold of value on Earth–metals, minerals, energy, water, real estate– are literally in near-infinite quantities in space. Planetary Resources’ mission is to gain access to natural resources of space by mining near-Earth-approaching asteroids. With technological advances that are coming out of exponential technologies and investors willing to bear the risk, small teams are now able to do what only governments and large corporations could do before. Our vision is to catalyze humanity’s growth both on and off the Earth. We’re breaking new ground.

Now is the time for us to gain access to these resources, and at the end the entire human race will be the beneficiary as we expand our reach beyond the Earth into the solar system. One asteroid may contain more platinum than has been mined in all of history. We’ve been searching for near-Earth objects mainly to assess the hazard of an impact on the Earth.

It turns out that most of these asteroids are not a threat to the Earth, but they do offer potential benefits. They are in Earth-like orbits that offer assessable resources that we can tap into, both for scientific knowledge and returning those strategic supplies to Earth. Resources from asteroids will add tens of billions of dollars annually to the global GDP.

Our plan for opening up the resources of the solar system is threefold. First, we’re going to identify all of the most valuable near-Earth asteroids– where they are, what they’re made of, and how to reach them. Second, we’re going to develop the technology and the capability to transform those resources into valuable materials. And third, we’re going to deliver those materials to the point of need, whether it’s a fuel depot orbiting the Earth or elsewhere in space.

Water sourced from asteroids will greatly enable the large-scale exploration of the solar system.

Our small and focused team will enable the commercial exploration of the solar system. We’re using experts who have gained their experience in NASA and the tech industry, and we’re keeping our goals simple and clear. Planetary Resources is applying commercial innovation to robotic space exploration. We have a need now for the knowledge of what’s on these asteroids.

There are potential resources in space, and the government is taking a scientific and measured approach to exploring them. We can really increase the knowledge that we get and the pace at which it comes back to us by involving commercial innovation and commercial visits to these asteroids. Planetary Resources will help ensure human prosperity by accessing the vast resources of space.

We are going to change the way the world thinks about natural resources.

Peter Diamandis on Mars to Stay

“I think privately funded missions are the only way to go to Mars with humans because I think the best way to go is on “one-way” colonization flights and no government will likely sanction such a risk. The timing for this could well be within the next 20 years. It will fall within the hands of a small group of tech billionaires who view such missions as the way to leave their mark on humanity.”

“The cost, complexity and risk of round trip missions is too high. I also am concerned that they typically result in flag-and-footprint missions which is what happened with Apollo. Government space mission budgets always get cut and compromised in the long run – it’s just the nature of the beast – and the science and meaningful long-term infrastructure is what gets cut out. With a one-way mission, you have to make sure you have the long-term infrastructure in place.”

“A private Mars mission is likely a five to ten billion endeavor and you won’t see multiple teams ever raising this level. If we ever re-invent launch technology to reduce the cost by 100-fold, then I think a “humans to Mars prize” would make a lot of sense.”

“I’m a big fan of heading to the asteroids first. In this light, I’d be very interested in a human outpost on Phobos before heading to the Martian surface. I do think this type of a human mission is within the scope, cost, and risk of governments.”

SpaceX’s Founder Elon Musk’s Caltech Commencement Address

From Elon Musk’s 2012 commencement address at Caltech: “What are some of the other problems that are likely to most affect the future of humanity? Not from the perspective, ‘what’s the best way to make money,’ which is okay, but, it was really ‘what do I think is going to most affect the future of humanity.’ The biggest terrestrial problem is sustainable energy. Production and consumption of energy in a sustainable manner. If we don’t solve that in this century, we’re in deep trouble. And the other thing I thought might affect humanity is the idea of making life multi-planetary.

“The latter is the basis for SpaceX and the former is the basis for Tesla and SolarCity. When I started SpaceX, initially, I thought that well, there’s no way one could start a rocket company. I wasn’t that crazy. But, then, I thought, well, what is a way to increase NASA’s budget? That was actually my initial goal. If we could do a low cost mission to Mars, Oasis, which would land with seeds in dehydrated nutrient gel, then hydrate them upon landing. We’d have a great photo of green plants with a red background [Laughter]. The public tends to respond to precedence and superlatives. This would be the first life on Mars and the furthest life had ever traveled.

“That would get people excited and increase NASA’s budget. But the financial outcome would be zero. Anything better would on the upside. So, I went to Russia three times to look at buying a refurbished ICBM… [Laughter] …because that was the best deal. [Laughter] And I can tell you it was very weird going late 2001-2002 to Russia and saying ‘I want to buy two of your biggest rockets, but you can keep the nukes.’ [Laughter] The nukes are a lot more. That was 10 years ago.

“They thought I was crazy, but, I did have money. [Laughter] So, that was okay. [Laughter] After making several trips to Russia, I came to the conclusion that, my initial impression was wrong about not enough will to explore and expand beyond earth and have a Mars base. That was wrong. There’s plenty of will, particularly in the United States. Because United States is the nation of explorers, people came here from other parts of the world. The United States is a distillation of the spirit of human exploration. If people think it’s impossible and it’s going to break the budget, they’re not going to do it.

“So, after my third trip, I said, okay, what we need to do already is try to solve the space transport problem and started SpaceX. This was against the advice of pretty much everyone I talked to. [Laughter]. One friend made me watch videos of rockets blowing up. [Laughter] He wasn’t far wrong. It was tough going there in the beginning. I never built anything physical. I never had a company that built something physical. So, I had to bring together the right team of people. We did all that, then, failed three times. It was tough, tough going.

“There’s more to happen for humanity to become a multi-planet species. It’s vitally important. And I hope that some you have will participate in that at SpaceX or other companies. It’s really one of the most important things for the preservation and extension of consciousness. It’s worth noting that Earth has been around for 4 billion years, but civilization in terms of having writing is only about 10,000 years, and that’s being generous.”

Neil deGrasse Tyson: "Audacious Visions"

Neil deGrasse Tyson: “Audacious Visions”:

Currently, NASA’s Mars science exploration budget is being decimated, we are not going back to the Moon, and plans for astronauts to visit Mars are delayed until the 2030s—on funding not yet allocated, overseen by a congress and president to be named later.

During the late 1950s through the early 1970s, every few weeks an article, cover story, or headline would extol the “city of tomorrow,” the “home of tomorrow,” the “transportation of tomorrow.” Despite such optimism, that period was one of the gloomiest in U.S. history, with a level of unrest not seen since the Civil War. The Cold War threatened total annihilation, a hot war killed a hundred servicemen each week, the civil rights movement played out in daily confrontations, and multiple assassinations and urban riots poisoned the landscape.

The only people doing much dreaming back then were scientists, engineers, and technologists. Their visions of tomorrow derive from their formal training as discoverers. And what inspired them was America’s bold and visible investment on the space frontier.

Exploration of the unknown might not strike everyone as a priority. Yet audacious visions have the power to alter mind-states—to change assumptions of what is possible. When a nation permits itself to dream big, those dreams pervade its citizens’ ambitions. They energize the electorate. During the Apollo era, you didn’t need government programs to convince people that doing science and engineering was good for the country. It was self-evident. And even those not formally trained in technical fields embraced what those fields meant for the collective national future.

For a while there, the United States led the world in nearly every metric of economic strength that mattered. Scientific and technological innovation is the engine of economic growth—a pattern that has been especially true since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution. That’s the climate out of which the New York World’s Fair emerged, with its iconic Unisphere—displaying three rings—evoking the three orbits of John Glenn in his Friendship 7 capsule.

During this age of space exploration, any jobs that went overseas were the kind nobody wanted anyway. Those that stayed in this country were the consequence of persistent streams of innovation that could not be outsourced, because other nations could not compete at our level. In fact, most of the world’s nations stood awestruck by our accomplishments.

Let’s be honest with one anther. We went to the Moon because we were at war with the Soviet Union. To think otherwise is delusion, leading some to suppose the only reason we’re not on Mars already is the absence of visionary leaders, or of political will, or of money. No. When you perceive your security to be at risk, money flows like rivers to protect us.

But there exists another driver of great ambitions, almost as potent as war. That’s the promise of wealth. Fully funded missions to Mars and beyond, commanded by astronauts who, today, are in middle school, would reboot America’s capacity to innovate as no other force in society can. What matters here are not spin-offs (although I could list a few: Accurate affordable Lasik surgery, Scratch resistant lenses, Cordless power tools, Tempurfoam, Cochlear implants, the drive to miniaturize of electronics…) but cultural shifts in how the electorate views the role of science and technology in our daily lives.

As the 1970s drew to a close, we stopped advancing a space frontier. The “tomorrow” articles faded. And we spent the next several decades coasting on the innovations conceived by earlier dreamers. They knew that seemingly impossible things were possible—the older among them had enabled, and the younger among them had witnessed the Apollo voyages to the Moon—the greatest adventure there ever was. If all you do is coast, eventually you slow down, while others catch up and pass you by.

All these piecemeal symptoms that we see and feel—the nation is going broke, it’s mired in debt, we don’t have as many scientists, jobs are going overseas—are not isolated problems. They’re part of the absence of ambition that consumes you when you stop having dreams. Space is a multidimensional enterprise that taps the frontiers of many disciplines: biology, chemistry, physics, astrophysics, geology, atmospherics, electrical engineering, mechanical engineering. These classic subjects are the foundation of the STEM fields—science, technology, engineering, and math—and they are all represented in the NASA portfolio.

Epic space adventures plant seeds of economic growth, because doing what’s never been done before is intellectually seductive (whether deemed practical or not), and innovation follows, just as day follows night. When you innovate, you lead the world, you keep your jobs, and concerns over tariffs and trade imbalances evaporate. The call for this adventure would echo loudly across society and down the educational pipeline.

At what cost? The spending portfolio of the United States currently allocates fifty times as much money to social programs and education than it does to NASA. The 2008 bank bailout of $750 billion was greater than all the money NASA had received in its half-century history; two years’ U.S. military spending exceeds it as well. Right now, NASA’s annual budget is half a penny on your tax dollar. For twice that—a penny on a dollar—we can transform the country from a sullen, dispirited nation, weary of economic struggle, to one where it has reclaimed its 20th century birthright to dream of tomorrow.

How much would you pay to “launch” our economy?

How much would you pay for the universe?

Bob Zubrin’s Closing Statements at the 13th Annual International Mars Society Convention (Twitter: #MSC2010 )

Mars Society Executive Director Lucinda Land: And most of all I want to thank you for coming here, ’cause I know it’s a costly thing to travel and to — I appreciate your time and your effort — and the expense of coming to our convention — and I really appreciate that you’re here and showing your support. And I look forward to seeing you next year, um, at our convention in Dallas. For the final statements I’d like to turn it over to Dr. Robert Zubrin. Please welcome him, thank you.

Mars Society President Bob Zubrin: So, ah, I’d just like to reiterate, and ah, this is not pro forma, my thanks to the people who organized this conference — who made it possible, the Ohio chapter especially — but also, of course, Pat Czarnik, Lucinda, and others that aren’t even here — Sue Martin and Freya Jackson…this stuff, it doesn’t happen by itself, and um, this was really a bang up job, and, I’m really grateful to the people who put up the effort. No one got a dime to get things done, and, a lot was done. So. I might want to mention on the subject of money we did raise about 11,000 dollars last night at the banquet, and uh, that’s a good thing — and that is also, obviously needed, but a demonstration of the kind of commitment that is needed more broadly and makes everything happen.

Now, um, lots been said at the convention here, and, there isn’t really that much to add, ah, that hasn’t been said, nevertheless it’s useful to underline the subject: we’re in a battle, um, it’s a big battle, ah, it’s an important one. We have an — possibilities for things to move in very different directions at this point. The situation was thrown into flux, ah, when Bush and Griffin left office — there was a certain program which was in place that — ffhhwwwwwt — was ripped up…and that program was not perfect from our point of view. Not — hardly. Anyone who’s been to these conventions knows that I’ve been quite critical of many aspects of it, but at least it was something– but at least it would have given us a heavy lift booster, a capsule, an interplanetary throw stage — about half the hardware set we would have needed to go to Mars. At least it was a way to have some form of progress in our space program.

The, um — what happened in February — it was a put up job! — John Holdren, Barack Obama’s Science Advisor — a long time enemy of human spaceflight, a long time enemy frankly of industrial civilization and technical progress — you can verify that, if you look up the books which he has co-authored with a man named Paul Ehrlich who’s an ardent advocate of the whole zero-growth thesis, that human growth need to be stopped, human growth, population growth, technical growth — this has all got to stop. And in fact he calls the United States an “over-developed country” that needs to be de-industrialized. If you read these books — they’re amazing — whenever they use the word “progress” they put it in quotes. And…in other words they can’t even say the word progress with a straight face. “Our more advanced civilization…” blah, blah, blah. Okay? Out of their deep concern for the people in Africa they want to prevent them from having to live in the conditions that we live in today…ah — and would prefer, actually, that it go the other way.

But the space program is — of course — the…well, the space program is two things, isn’t it. NASA…the government program — which after all is the main space program which actually exists — as opposed to the private one, which we’re all hoping will emerge — but the one which has existed up to now is the NASA program. And it has two sides to it, doesn’t it. There is — as its opponents say — this huge wasteful bureaucracy and it does wasteful things and it is bureaucratic and you name it — on the other hand, there is NASA as the symbol, of the pioneer spirit, there is NASA as the symbol of the “can do” American spirit: WE CAN DO ANYTHING.

And…ah…of self-reliance, ingenuity — the ability of progress to make things possible that were never possible before. Okay…and…ah, after all…when we went to the moon what was it fundamentally saying? “FREE PEOPLE CAN DO ANYTHING. THERE IS NO CHALLENGE THAT’S BEYOND US.” And there are no limits to human aspirations, and human aspirations do not need to be constrained in order to, ah, fit within certain limits, that some people might want to impose upon us. There’s those two aspects. So what?

So, NASA — not as bold as it was in the 60s by any means — but still, under the previous plan, we’re returning to the moon — “Ok, we’re returning to the moon. We’re going back to where we were the last time we made that statement” — and presumably we would go on from there. And they killed that program. And they killed it: will malice of forethought. Look, there has been a certain number of people in this country, who have said, “We have other needs, the space program is absorbing all this enormous amount of money” — even though frankly it’s not all that much, it’s half of a percent of the Federal budget at this point — but still, “19, 20 billion dollars is not pocket change, we would like to spend it on something else.” I can respect that point of view. There are other needs to be met and one could debate what the money should be spent on.

But — they didn’t do that. They didn’t cut NASA’s budget in order to spend the money on social programs. Or housing projects or highway repairs or body armor for the troops — or tax reductions. They didn’t cut the NASA budget at all — they just aborted the program. Okay. And instead of having NASA spend its money to restate — what it said before, to restate that America still has the right stuff — that we still adhere to the pioneer spirit, that we’re still willing to take great risks to do great things, and prove that the impossible is possible…okay…they ah, said, “Fine. We’ll give you the money, because we know all you really care about are your jobs — so we’ll give you three billion a year to refurbish the Shuttle launch pads after the Shuttle stops flying.” I’m not making this up.

Originally they wanted to kill the Orion altogether — but finally when there was push back — they said, “Well, look, we understand, you don’t want to be able to send Americans to orbit…all you care about are your jobs, so we’ll give you your jobs, you can have your Orion money, we don’t care, just so long as it cannot take astronauts to orbit — so we’ll give you an Orion that goes down and not up. I mean this is: incredible. I mean I’ve never seen anything like this. Carter — wrecked the space program — but at least he spent money and spent it on something else. We can argue about whether that was a good idea — I don’t think it was — but at least it was…ah, ah, on the level, in the sense of saying, “I want to take this money and spend it on something that I think is more valuable.” Instead, “Well, okay…you don’t like the Shuttle program shutting down, so why don’t we keep the Shuttle program going except we won’t fly any Shuttles, or, maybe we’ll fly one.” You know…and, so, this is incredible. It is…degrading. Okay, to NASA. It is degrading to everyone in NASA to be told this: “You’re only objecting to the shut down of the program because it’s your paycheck — ‘well, we’ll give you your paycheck, how’s that? We just don’t want you to accomplish what you claim you’re trying to accomplish.'”

Think how degrading that is. And yet they cynically do exactly that. And, ah…now, you know, uh, Cicero said, “Gifts make slaves.” Okay. You give people handouts — and they become depended, they loose their integrity, they loose their self-reliance, they loose their ability to do anything. Okay. The, the — and they become something less than what they were before. And the space program…if we have a space program, which is just taking handouts — its not being asked to do anything — its going to become something less than it was before and visibly so.

And, while it was debatable whether we should be spending four billion dollars a year on a Shuttle program that was launching six Shuttles to orbit a year — because that really is frankly pretty inefficient, at Shuttles, at, say, 750 million a launch — to launch the same thing a proton could launch at 70 million each — it becomes surreal when one talks about paying 4 billion dollars a year to launch 1 Shuttle, or, no shuttles. Okay? Ah…and…redecorate the pads. Because all you people really care about is the jobs….

“This is not space exploration this not a space program, and you people are not engineers you are welfare recipients.”

The…ah…so…now…the positive side of this…was that it was sufficiently outrageous that it outraged a lot of people. A lot of people. People in Congress — people in the President’s own party — Neil Armstrong, who’s been a total recluse for the past, you know, 40 years — came out and said, “I can’t accept this!” This guy has never said anything. Okay? Um…he came out and said it.

Now…we were…true to form…basically first to denounce this policy. First. I am proud to say. Okay. First to denounce the Augustine policy — the Augustine board was created — John Holdren appointed the Augustine, appointed members of the Augustine commission, and they reported to him. He told them when they gave him the answers he wanted. Okay.

This thing with the flexible path? What’s that?? Flexible path. Let me tell you something, I worked for Norm Augustine at Martin Marietta Company. And he did not believe in the flexible path then. He did not believe in having programs have no schedules. He did not believe in programs having no specific goals. This is not Norm Augustine’s management philosophy in anything that he actually cares about.

So to say that this is the program that the Space Shuttle — that the space program should adopt: no concrete objectives, no concrete goals, “work on interesting things and let us know when you are ready to do something”…okay…sure…”we’ll just give you money and you don’t have to do anything, by any particular time.” No. This is a put up job. I denounced it in Space News as a Path to Nowhere when they were basically enunciating it, and then of course when the administration came out with it as their policy.

But now, we have allies. We have allies precisely because the policy is so bad. Okay…ah. They have outraged so many people, and that has created flux in the situation. If they had just come out with something that was half bad — we would have been left isolated. The…a lot of people would have said, “I guess that’s okay, that’ not too bad, let’s move on…” but no, it’s been too crazy.

So we have first the Senate committee and now the full Senate — dominated, almost 60 percent by members of the President’s own party — pass, okay, a…authorization bill that…completely contradicts the administration’s policy. Says, “No! It is wrong! We are not doing it!” Okay…ah…now…unfortunately…okay, it compromises. Because…well, you know, “they’re saying we get nothing, we’d like something, something is better than nothing…and we’re willing to compromise.”

But still, they’ve got a bill in there with money to develop heavy lift. We have to get that to pass. Okay. We have to deliver this defeat, okay, to the Obama administration, and, ah, let them know what the score is. That they can’t just take a major American institution — that, even more than an institution — a symbol, of a great American value. The pioneer spirit.

You know…we went to bat for Hubble against Sean O’Keefe. And it wasn’t just that he was willing to destroy 4 billion dollars worth of the tax payer’s property — which was criminal — but, that he was, undermining — abandoning — two or three critical things. One, NASA as an organization committed to the exploration of the Universe, when they’re abandoning their premiere instrument, their premiere project. Abandoning NASA as an embodiment of the pioneer spirit. –I mean, after all, how’s NASA ever going to the moon or Mars if it is afraid of ever going to Hubble? “This is too risky for us.” I mean, this was the explicit reason: it is too risky for us. Literally, the excuse was: fear. And to say this is the level of timidity at the leadership that was accepted — the philosophy — of an organization which is supposed to be committed to exploration. Okay? And then that takes you to the broader issue — well, two broader issues: which is, the value of the search for Truth and the commitment to…Courage.

Courage is a virtue. Okay? It’s one of the four classical virtues. Justice, courage, wisdom, moderation. Those are the four virtues. Christians add faith, hope, and charity. But these are the four virtues of the Ancient Greeks. And this — Courage — is a fundamental virtue. It is a virtue, without which, none of the other virtues are operable. It is arguably the most important virtue. Okay…it does no good to be Just, if you lack the courage to do Justice. It does no good to be wise, if you lack the courage to do what you know you should do. And so forth. –He was willing to abandon that.

And then finally — Hubble — it is not just a scientific achievement, it is a symbol, of humanity’s commitment, to the search for Truth. It is in a sense the most noble artifact of the 20th Century. It is for us what the Gothic cathedrals were…to…the people of the high Medieval ages, to symbolize their most highest ideals and the aspirations of that civilization. This is the greatest thing for us. You know, people five hundred years from now are not gonna look at our paintings from this period of time — Jackson Pollack — I tend to doubt very much they will think very much of our popular music. And they won’t care at all about our various geo-political struggles among nations — most of which will no longer exist, in their current forms. But they will look at Hubble, and the images it brought back of the Universe, and say, “These people were noble.” –And he was going to abandon that.

And similarly, NASA, as the human space flight program — as an institution — is not merely what it does…okay…because frankly, except for Apollo and Hubble it hasn’t done that much. Okay. But…it’s…it is what it stands for in terms of defining who we are. It’s about who we are. Okay? That’s what it is. That’s why Americans support NASA — fundamentally — it’s not the weather satellites…it’s not the reconnaissance satellites…it’s to some extent — they do like getting back the images of the Mars Rovers and things…and they are curious about some of the answers we’re getting, and they’re hopeful about opening up a new frontier in space, yes…but ultimately it is about who we are.

Yes, we do this because this is who we are — and frankly, this is who we have to be if we are ever going to open the space frontier. So, what you had here, was, an attack on not just NASA but on the American identity. The identity of the pioneers of a frontier. Okay. The…um — so it’s got to be repelled. With, losses to the enemy. So this is the immediate crisis. I think we can win it. We won Hubble — we were the first people to stand up for Hubble, except for astronomers. “Oh you’re astronomers, of course you want a stupid telescope.” Okay…we were the ones who said, “okay, there are issues here that go way beyond the issues of Mikulski’s district.”

This is about who NASA is — this is about who America is. And this is about — this is not just about — you know, Ares 1. I don’t care about Ares 1. You know, frankly I was never that enthusiastic about it — I thought Orion was oversized…it should have been sized down to fit on an Atlas Five, which we have. And so on…you can make all sorts of criticisms like this — but ultimately, they didn’t say that…they didn’t rationalize or try to improve Giffin’s argument…they just said, “This is not who we are.” Okay. Umm…well…it’s got to be who we are…we’ve need to win this.

We’ve got to do what we’ve done on several occasions in the past — which is to take the trouble and go and meet with Congressmen in their home offices…and this is entirely possible to do…and talk to them about this. The bottom line is…NASA needs to have a goal…a goal that is proximate enough to give meaning to its activity…that goal should be Humans to Mars. And the first and most critical — ah, piece of technology that needs to be developed, that is, heavy-lift. Okay. The, the, the — and, and the Senate bill has the money to do it. So, bottom line is, we want you to support that. We go in there and give briefings to Congressmen and they ask us, “What do you want us to do?” –That is what we want you to do. That’s what we would like them to do now.

We’d like them to go further — sure. We’d like them to be champions for our vision — okay, of course…this country needs to set its sights on Mars…we need to embrace the challenge that has been staring us in the face since 1973 and which we have largely shirked. Okay. We need to do that. Okay, we — I mean look, we have everything we have because of our predecessors who had the guts to come across an ocean and build a civilization in the wilderness. A Grand Civilization. Which, not only includes a continental nation committed to liberty — and, whose bayonets have held up the sky for liberty around the world for the past half-century — but, a place that tens or hundreds of millions of people have come to realize liberty for themselves. A place which has demonstrated liberty to the world, so that its fundamental values have been emulated around the world — and laid out the future for humanity in that respect. A place whose inventors have created the modern world — because — it is a place that embraces challenges in all areas, okay, a county that was responsible for inventing electricity, and the telegraph,and the telephone — and I might add, two inventors who came from Ohio: Thomas Edison, who was born here, and of course the Wright brothers, who gave us flight, and gave us motion pictures, and all kind of things — and, furthermore, made the statement that: progress is good, and, that there are no barriers, to a people who embrace challenge in this way — and are wiling to not accept that things are impossible. Okay. Flying. Flying into the air, flying to the moon.

We chose Dayton because as different as the Wright brother’s accomplishment is from the Saturn Five they were both at least in one sense completely emblematic of the same thing — I mean, human flight, realizing an age old dream, reaching for the moon. They were two things which were considered emblematic of what was impossible. They were age old expressions of what was an impossible thing. Okay. And one was invented here, the other was piloted by a guy born here. But — this is the values we’ve got to defend, okay; this is…the message that counts.

And..you know…we are not that many people, but, um, all great things start as little things, all great movements start as small movements. Okay, and, it is…the advocates of ideas — which are not generally accepted — who are those who move humanity forward. Those people who are content with the world as it is, leave the world as it is.

So we have a critical role, as small as it is, as modest as our financial resources might be — we nevertheless represent an idea, which is coming to be as powerful a dream as humans flying in the air once was. The — not just the Freedom of the skies, the Freedom of the Universe. The Freedom of a society fundamentally without limits. That is not limited to one planet — that has before it this enormous prospect of an infinite universe of worlds. The Beichman Group is going to give their results in January — my guess is they’ll report hundreds of planets. These won’t be Earth-like yet because they’re too close to their sun — but a year later, when they’ve had more time and the planets can go longer periods, there’ll be more and more and more. We live in an infinite universe of worlds — and, the ability to show then, that these are attainable…that…ah, that they are not an infinite universe which is out of reach, but an infinite universe which is fundamentally within reach.

This is ultimately what the significance of Mars is: that we do not live in a limited universe of limited resources where human aspirations need to limited to conform to such limits, and various regulatory authorities need to be empowered to enforce the acceptance of such limits, and so forth; but rather: we live in a world of infinite possibilities, where, rather than human existence needing to be preserved by suppressing human aspirations and humanFreedom, rather human existence can be enhanced to the greatest by endowing as many people as possible with Freedom and the skills and education required to use it. And ultimately everything hinges on this. Everything. The issue here is — I’ve commented on this in the past, but I just need to restate it. This thing is more important than Mars colonies, as such — as important as they may be. This thing is about the general view of the future people now have. And the general view of the future that the people now have will determine their actions not in the future — but today.

Is it a good thing or a bad thing that the sons and daughters of Chinese peasants are going to college and becoming scientists and engineers? The person who says, it is — that there are limited resources in the world, says that is bad. That development of countries like China and Egypt should be surpressed — “because these people are going to be as rich as us, they’ll be as educated, they’ll have automobiles and they’re going to use resources and oil and all this stuff and we’ve got to do everything we can to screw them up. Okay. So they do not get what we have.” Okay. On the other hand…if you believe, that, the resources accessible to humanity are determined only by our creativity then you say it is a wonderful thing that the sons and daughters of Chinese peasants are becoming scientists and engineers. Okay. Because right now, America with four percent of the world’s population, is creating half of the inventions in the world. And — as honorable as that may be, and as proud as an American I may be of that fact — that is not a good thing, that is a bad thing.

Human progress is being slowed down by the fact that most of the world — the potential — of most of those people to make contributions to progress is limited, by their lack of development, and by their lack of freedom. And — the…it would be a great thing for us — just imagine all the progress there could be, and the advance of the human condition there could be — if all these people all over the world who are now unable to contribute to progress, because of their circumstances, were.

So, at that point you say, “Well, we’re friends with the Chinese. We don’t need to go to war over oil — or try to wreck their economy, or them viewing us as trying to wreck their economy. This goes both ways by the way…I mean, these views, they become global. If everyone believes that resources are limited — you have a world in which every Nation is the enemy of every Nation, every race of every race, and ultimately every person of every person. Every new baby born in the world is a new enemy because it’s going to eat something you want to eat. Okay…its a world of hate, and tyranny, and ultimately its a world of war.

If, on the other hand, people understand, that, wealth is not something that exists in the ground — it’s something that’s created with our minds. That human beings fundamentally are not destroyers but creators…then, every nation is ultimately the friend of every nation, and every race of every race…and ever new person born into the world is not a threat but a new friend.

And this is the mental framework which will determine whether we make the 21st Century the greatest era of human progress or a century of hell. That’s the choice before humanity, our specific role…is to use, the Mars Project, to demonstrate, once again, the virtue of humanity. Thank you.

Curiosity and Cameron

“I think any kind of exploration should always try to acquire the highest level of imaging. That’s how you engage people — you can put them there, give them the sense they’re standing there on the surface of Mars.”

.

For obvious reasons the pro-active visionary heroics of Oscar-winning director James Cameron have become a running theme on this blog. The director of “Avatar” and many other sci-fi flicks, “Titanic,” and technologically demanding undersea documentaries, is now helping NASA develop a high-resolution 3D camera for the next Mars rover, SUV-sized Curiosity, due to launch in 2011.

.

Remember the beautiful Mars imagery NASA’s Mars rover, Spirit, captured during its journey to the Red Planet? Now imagine high-definition color 3D video from the surface of Mars at eye-level, in motion, at walking pace: sunrises and sunsets, stars after midnight, vistas stretching for miles.

.

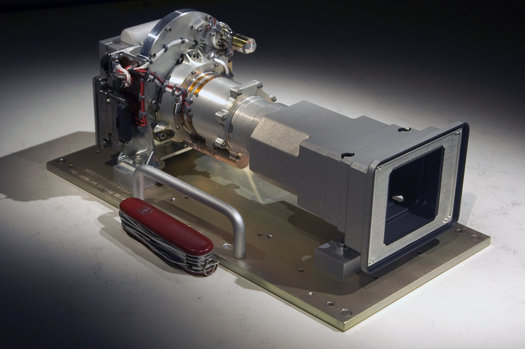

“The fixed focal length [cameras] we just delivered will do almost all of the science we originally proposed. But they cannot provide a wide field of view with comparable eye stereo. With the zoom [cameras], we’ll be able to take cinematic video sequences in 3D on the surface of Mars. This will give our public engagement co-investigator, James Cameron, tools similar to those he used on his recent 3D motion picture projects,” said Michael Malin of Malin Space Science Systems, Inc, the company which developed the Mastcams.

“[NASA Administrator Bolden] actually was really open to the idea. Our first meeting went very well. It’s a very ambitious mission. It’s a very exciting mission. (The scientists are) going to answer a lot of really important questions about the previous and potential future habitability of Mars.”

“We so desperately need not to blow it,” Cameron said of the first opportunity in decades to consider moving human exploration beyond low Earth orbit. Cameron has lamented that space exploration stalled — because of political compromises — after the Apollo moon landings. Rather than being a jumping off point to future great adventures, the space shuttle and International Space Station ultimately “formed a closed-loop ecosystem for self-justification.”

Now, the agency has a chance to move beyond that and chase mankind’s “greatest adventure” — landing humans on Mars.

“Where does the money come from? From working people, with mortgages and kids who need braces. Why do they give the money? Because they share the dream.” They need reasons to stay engaged: from telling them the ways space exploration has provided them with tools that improve their daily lives to helping them to be more interactively involved in the missions.

NASA’s focus has been on hardware instead of people, partly because the agency shields its people from the public. Instead, in an era when American kids and adults need inspiration, NASA needs to do a better job of selling its astronauts and scientists as heroic people.

“Our children live in a world without heroes,” he said. “Your kids need something to dream about. We need this challenge to bring us together.” I think that any kind of exploration should always try to acquire the highest level of imaging. That’s how you engage people — you can put them there, give them the sense that they’re standing there on the surface of Mars.”

“The [1997] Sojourner Rover became a character to millions of people, a protagonist in a story. How long is it going to survive, could it perform its mission? It wasn’t anthropomorphic in any way, there was absolutely no emotion in a little solar powered machine that was being commanded from eighty million miles away, and yet people thought of it as a character. The reason we thought of it as a character is that it represented us in a way. It was our consciousness moving that vehicle around on the surface of Mars. It’s our collective consciousness — focused down to that little machine – that put it there. So it was a celebration of who and what we are. It takes our entire collective consciousness and projects it there – to that point in time and space. That’s what the Sojourner Rover did.”

“I was involved in a private company that was going to try to land two rovers on the Moon. That collapsed in the dot com crash – they ran out of money. I’m loosely involved with people who are going to be doing future robotic missions to Mars. I’m involved in terms of imaging, and of how imaging might be improved in terms of story telling. I’ve been very interested in the Humans to Mars movement –the ‘Mars Underground’ — and I’ve donea tremendous amount of personal research for a novel, a miniseries, and a 3-D film.”

Mars is real, non-threatening, a living character with which humanity must become familiar and comfortable. Stay tuned for a forthcoming post explicitly about Cameron’s Mars film work, yet again.

Note the Destination Boring People Advocate…Isaac Asimov debate at the Hayden Planetarium (thanks to Landmark Pictures)

Factual corrections to points made by Paul Spudis: eight week round-trip missions to NEAs have been proposed (see earlier posts on this blog); most asteroids rotate at very, very low speeds; most do not have “co-orbiting clouds of debris;” resources will be collected at asteroids and processed in artificial ‘gravitational’ environments at LEO. These are exciting, solvable engineering challenges. Solvable.

Bob Zubrin:

“From a technical point of view, we’re much closer today to sending humans to Mars than we were to sending men to the Moon in 1961. […] While there are resources on the moon there are vastly more on Mars. There’re continent sized regions on Mars that are 60% water in the soil. There’s complex geological history which has created mineral ore. There’s carbon, which is necessary for life and for plastics. There’s nitrogen. There’s a twenty four hour day. […] The reason why it is important to do something as hard as exploring and ultimately settling Mars, is because of what it would do for opening up and creating the prospect of a human future with an open frontier rather than a limited frontier of a world of limited resources, in which choices are becoming ever closer and smaller and freedom is ever more limited.“

If Lunar advocates were at a bar they’d drink alone. Soda. After having attended several space-related conferences each year for over a decade, one characteristic of moon-first advocates which has been unfailingly predictable: they are boring as hell.