“Falling in Love With Mars: A Tribute to Ray Bradbury,” by Joi Weaver

I remember when I fell in love with the Red Planet. It wasn’t seeing pictures from Sojourner or the MER rovers. It wasn’t from any scientific data at all.

I fell in love with Mars when Spender quoted Byron in a dead Martian city at at night, in the first chapters of The Martian Chronicles.

“So we’ll go no more a-roving,

So late into the night,

Though the heart be still as loving,

And the moon be still as bright.

For the sword outwears the sheath,

And the heart outwears the breast,

And the soul must pause to breathe,

And love itself have rest.

Though the night was made for loving,

And the day returns too soon,

We’ll go no more a-roving,

By the light of the moon.”

At that moment, it didn’t matter to me whether or not Mars had ever known life. It didn’t matter if Mars was a dead world. Mars was cold, dry, open, and I loved it.

I devoured the rest of The Martian Chronicles, watching the sudden growth of trees planted by an early colonist, cheering as Mars became a home for the homeless and disenfranchised of Earth. Ray Bradbury wove an intricate narrative, bringing Mars to life through the stories of people of every conceivable background. As I read, Mars became more than a red dot in the night sky, more than a cold dead world. Mars became home.

At the end of The Martian Chronicles, Earth becomes embroiled in yet another war, one that threatens to wipe out all life on the planet. Most of the Mars dwellers return, even though they know it means leaving Mars behind forever. But a few stay. In the final scene of the book, a single family sets out on an adventure to “find the Martians.” At the end of their trip, they look down into a pool of water and see their own faces looking back. “The Martians were there–in the canal– reflected in the water. Timothy and Michael and Robert and Mom and Dad. The Martians stared back up at them for a long, long silent time from the rippling water…”

Bradbury often stated that he did not write science fiction stories; instead, he insisted, he wrote people stories. The people in his stories might live on Earth in the future, or on a spaceship, or on Mars, but they were still people: fallible, but always familiar. A reader might not identify with a robotic explorer or a technological genius; but a young woman, boarding a ship to travel to Mars and begin life on the new frontier with her husband, is a character any reader can connect with.

Bradbury didn’t just feed the imagination or paint a picture of a world to be explored. He flung wide the doors to the universe, and filled it with little bits of Earth: people, places, books, art, music. He showed us the cosmos and made it feel like home. He reminded us that it is not enough to survive on a new world through technological prowess, we must bring all of the best of humanity with us, or our new worlds will remain nothing but outposts.

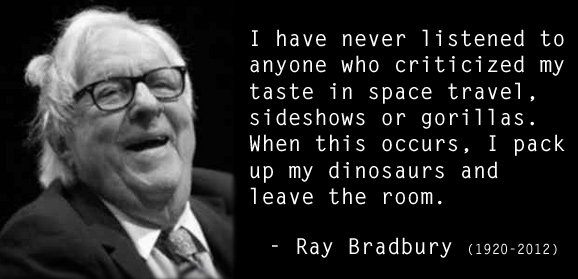

Farewell, Ray Bradbury. And thank you.